This newsletter focuses on movement methods and techniques. What are they? What influences them? How to develop them?

Hi everyone,

Welcome to those that are new to this newsletter, the aim is to write one each month which hopefully gives people the have chance to read before the next one comes along!

Wow, we are almost a quarter of the way through the year, and I know I am struggling to keep up with my new year resolution of “getting stuff finished”…

If you are reading this online, and would like the next one to land in your email, then please click this link. Alternatively, if you have received this via email and wish to unsubscribe the details are at the bottom!

Finally, as always thanks for your support…

Let’s go!

Methods and Techniques?

In applied systems thinking, the terms ‘method’ and ‘technique’ are defined as:

- method – a particular procedure for accomplishing or approaching a task

- technique – a way of carrying out a particular method

In human movement, these two are often combined and referred to as ‘technique’.

For example…

- method – common movement pattern

(e.g. spin bowling technique, fast bowling technique, power hitting technique, etc) - technique – individual movement pattern

(e.g. specific technique individual adopts to complete the tasks above)

Although using technique for both is not wrong, this creates confusion.

For example, in fast bowling, research on the optimal technique (method) has highlighted the fastest bowlers have the fastest run-up speeds…

Yet, the optimal individual technique is not to run in as fast as possible or as fast as someone else.

One of my favourite quotes on this issue is by Butch Harmon, the golf coach, who says ‘that if you want to play golf (method) like Tiger Woods (technique) you better be Tiger Woods.’

To ensure that safe and suitable coaching applications are employed it is important to understand how the science, theory and opinions apply and differ for methods and techniques.

What influences method frameworks?

From my experience, there are generally three approaches coaches build their own method frameworks (understanding) for a movement pattern:

- Their own experiences – “that’s the way I learnt/did it”

One of the most common influences on the way we teach is how we were taught or learnt knowledge. - What a similar sport or the best do – “imitating the best”

There’s loads of phrases around imitation but regarding learning Aristotle wrote ‘human beings are the most imitative creatures in the world, and learn at first by imitation’. - Human movement principles – “that’s what the science says”

Knowledge. Theoretically understanding what is the best way for our bodies to move to complete the task. (See February 2023’s newsletter on kinetic chains for instance)

In practice, I use a combination of all three to assess my practice, reflect, and evolve my framework as my knowledge around the movement pattern evolves.

Once developed this can also be used to question technique – why is it different?

What influences individual techniques?

Brace yourselves…. here comes another engineering concept with a funky name!

(Sorry I have a maths degree and love systems theory)

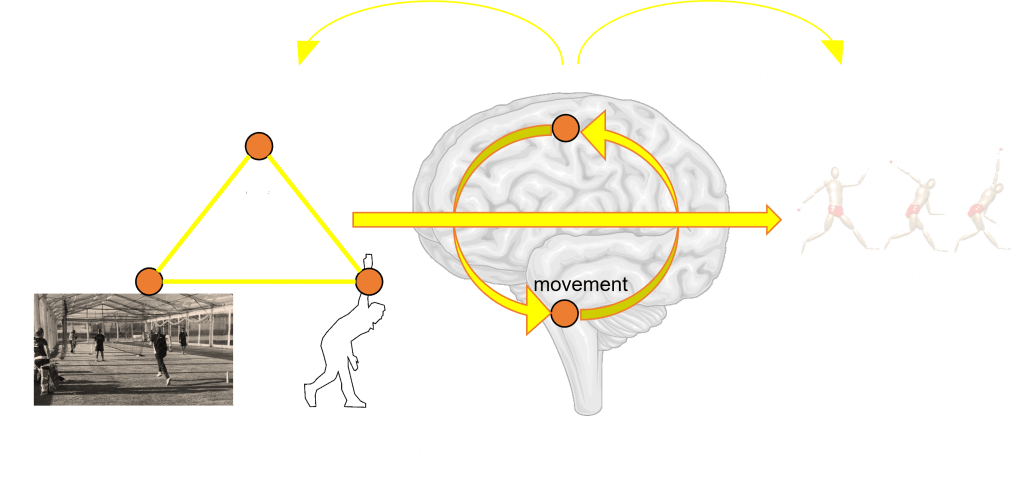

My theoretical framework for human movement is structured on dynamical systems theory.

Dynamical system theory is a branch of mathematics which allows the behaviour of complex systems to be described using constraints.

There’s a great paper on this theory being applied to human movement systems by Davids et al., 2003 (see Movement systems as Dynamical Systems ).

They adapt Newell’s model (1986) which suggested that the behaviour of a dynamical system is shaped by three types of constraint:

- Organismic – those relevant to the individual

(e.g. size, strength, range of motion etc.) - Environment – those relating to the environment the system within

(e.g. indoor, outdoor, equipment, etc.) - Task – the constraints based on the movement task

(e.g. outcome of task, rules of the sport etc.)

This model was adapted to include movement coordination based on previous experience of the movement by Davids et al., (2003).

This relates to the intrinsic movement patterns that individuals learn and develop as they gain information from producing the movement.

When attempting to produce a movement pattern, our brains consider all these factors, and produce a technique (performance) which aims to deliver the desired outcome.

In sport, the success of the technique to complete the task, it is often analysed and judged.

It is important to build and develop the understanding of how these constraints and movement patterns impact our method frameworks.

For example, there is emerging research which suggests the movement patterns females adopt in bowling and batting may differ from their male counterparts.

My framework has therefore evolved based on this understanding of how the organismic constraint differences impact technique.

How?

Well as Leonardo Da Vinci, once said ‘To develop a complete mind: Study the science of art; Study the art of science. Learn how to see. Realise that everything connects to everything else.”

For me this takes the following approach…

Study the science of art; Study the art of science... interact with the science, the theory and opinions. There is value in all of it.

Learn how to see… acknowledge the information in the light it is displayed (knowledge vs opinion). We do not know all the answers, people theorise, and science investigates. Appreciate social media is a great place for theories… but many are not yet proven.

Everything connects to everything else… develop links between methods and techniques. Question what you see and why they do it differently. Compare with your experiences, what others do, and what the science says.

That’s all for this month

To recap:

To ensure that safe and suitable coaching applications are employed it is important to understand how the science, theory and opinions apply and differ for methods (the common movement pattern) and techniques (individual movement patterns).

In practice, I use a combination of my own experiences, how others do it, and scientific principles to develop my method frameworks.

I use a dynamical systems theory approach to question how techniques are influenced by organismic, environmental and task constraints, as well as previously developed movement coordination patterns.

Thanks for reading.

Paul